Bruger:Kalaha/sandkasse1

"7/7" omdirigeres hertil. For kalenderdagen, se 7. juni.

"7/7" omdirigeres hertil. For kalenderdagen, se 7. juni.

| Terrorangrebet i London 7. juli 2005 | |

|---|---|

Redningstjenester i aktion ved Russell Square Station 7. juli 2005 | |

| Sted | London, Storbritannien |

| Dato | 7. juli 2005 kl. 08:49 - 09:47 (UTC+01:00) |

| Mål | Offentligheden ombord på London Underground-tog og en bus i det centrale London |

Type af angreb | Massemord, selvmordsangreb, terrorisme |

| Våben | TATP |

| Døde | 56 (inkl. de 4 gerningsmænd) |

Sårede | 784 |

| Gerningmænd | Hasib Hussain Mohammad Sidique Khan Germaine Lindsay Shehzad Tanweer |

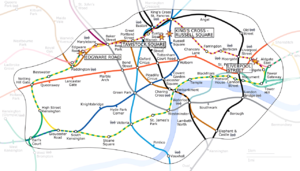

Den 7. juli 2005 blev der gennemført et større terrorangreb i London, nogle gange refereret til som 7/7, bestående af en række koordinerede selvmordsbombeangreb i det centrale London, der var målrettet civile brugere af det kollektive transportsystem i myldretiden.

Om morgenen torsdag den 7. juli 2005 detonerede fire islamistiske ekstremister hver for sig tre bomber kort efter hinanden ombord på London Underground-tog på tværs af byen, og senere en fjerde på en dobbbeltdækkerbus på Tavistock Square. 52 personer blev dræbt og mere end 700 yderligere blev såret under angrebene, hvilket gør det til det værste terrorangreb i Storbriannien siden bombningen af Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie, Skotland i 1988, ligesom det er landets første islamistiske selvmordsangreb nogensinde.

Eksplosionerne blev udløst af hjemmelavede bomber baseret på organisk peroxid, der var anbragt i rygsække. Bombeangrebet blev to uger senere efterfulgt af en række angrebsforsøg som ikke forårsagede sårede eller beskadigelser. Angrebet 7. juli indtraf dagen efter, at London var blevet udpeget som vært for De Olympiske Lege i 2012, hvor buddet havde fremhævet byens multikulturelle omdømme.[1]

Angreb

[redigér | rediger kildetekst]London Underground

[redigér | rediger kildetekst]Kl. 08:49 detonerede tre bomber ombord på London Underground-tog indenfor 50 sekunder:

- Den første eksploderede på et 6-vogns C69/C77 "sub-surface"-tog på Circle line, nummer 204, der kørte mod øst mellem Liverpool Street og Aldgate. Toget havde kørt fra King's Cross St. Pancras ca. otte minutter tidligere. På eksplosionstidspunktet var togets tredje vogn ca. 90 m inde i tunnelen fra Liverpool Street. Det parallelt liggende spor på Hammersmith & City line mellem Liverpool Street og Aldgate East blev også beskadiget under eksplosionen.

- Den anden bombe eksploderede i den anden vogn på et andet 6-vogns C69/C77 "sub-surface"-tog på Circle line, nummer 216, som lige havde kørt fra perron 4 på Edgware Road og kørte mod vest mod Paddington. Toget havde kørt fra King's Cross St. Pancras ca. otte minutter tidligere. Der var adskillige andre tog i nærheden på eksplosionstidspunktet: et østgående Circle line-tog (ankommende til perron 3 på Edgware Road fra Paddington) passerede ved siden af det bombede tog og blev beskadiget,[2] ligesom en væg senere kollapsede. To øvrige tog var på Edgware Road: et uidentificeret tog ved perron 2 og et sydgående Hammersmith & City line-tog, der lige var ankommet til perron 1.

- En tredje bombe blev detoneret på et 6-vogns 1973 "tube"-tog på Piccadilly line, nummer 311, der kørte mod syd fra King's Cross St. Pancras til Russell Square. Bomben eksploderede ca. et minut efter toget afgik fra King's Cross, hvor det havde kørt ca. 450 m. Eksplosionen indtraf i den bageste ende af togets foreste vogn (nummer 166) og beskadigede bagenden af denne vogn så vel som fronten af den næste.[3] Tunnelen blev også beskadiget.

Det blev først troet, at der havde været seks eksplosioner, i stedet for tre, i Underground-netværket. Busbomben bragte den rapporterede total op på syv. Det rette antal blev dog klarlagt senere på dagen. Den fejlagtige beretning kan tilskrives at eksplosionerne skete på tog, der var mellem stationer, hvorved kvæstede passagerer flygtede fra begge stationer, hvilket gav indtryk af, at der var sket en hændelse begge steder. Politiet reviderede også eksplosionstidspunkterne, efter at de førte meldinger havde indikeret, at de indtraf over en periode på næsten en halv time. Dette skyldtes forvirring hos London Underground (LU), hvor de først troede at eksplosionerne var forårsaget af overspændinger. En af de første meldinger fra minutterne efter eksplosionerne involverede en person under et tog, mens en anden beskrev en afsporing (begge dele indtraf, men kun som følge af eksplosionerne). LU udsendte en gul alarm kl. 09:19 og begyndte at indstille togdriften på netværket med ordre om, at togene kun skulle køre til den næste station.[4]

Bomberne have forskellig effekt på tunnelerne, hvilke skyldes tunnelernes forskellige karakteristika:[5]

- Circle line er en "cut-and-cover"-tunnel beliggende ca. 7 m under overfladen. Da tunnelen indeholder to parallelle spor, er den forholdsvis bred. De to eksplosioner på Circle line kunne formentlig lukke deres energi ud i tunnelen, hvilket reducerede deres ødelæggende kraft.

- Piccadilly line er en dybtliggende tunnel, op til 30 m under overfladen og med smalle (3,56 m) enkeltsporede "tubes" og kun 15 cm fri bredde. Disse indelukkede omgivelser reflekterede kræfterne fra eksplosionen og koncentrerede effekten.

Bussen på Tavistock Square

[redigér | rediger kildetekst]

Næsten en time efter angrebe på London Underground detonerede en fjerde bombe på det øverste dæk af en linje 30 dobbeltdækkerbus, en Dennis Trident 2 (flådenr. 17758, registreringsnummer LX03 BUF, to år gammel på daværende tidspunkt) opereret af Stagecoach London og kørende på sin rute fra Marble Arch til Hackney Wick.

Tidligere havde bussen kørt gennem King's Cross-området, da den kørte fra Hackney Wick til Marble Arch. Ved sin slutdestination vendte bussen rundt og begyndte på returruten til Hackney Wick. Den forlod Marble Arch kl. 9 og ankom til Euston Busstation kl.0 09:35, hvor menneskeskarer var blevet evakueret fra undergrundsbanen og steg på busser.

Eksplosionen indtraf kl. 09:47 på Tavistock Square og flåede taget af og ødelagde den bageste del af bussen. Eksplosionen foregik nær BMA House, hovedkvarteret for British Medical Association, på Upper Woburn Place. En række læger og medicinsk personale i eller nær bygningen ydede straks førstehjælp.

Vidner udtalte, at de så "en halv bus flyve gennem luften". BBC Radio 5 Live og The Sun meldte senere, at to sårede buspassagerer sagde, at de så en mand eksplodere inde i bus.[6]

Bombens placering inde i bussen betød, at køretøjets front forblev stort set intakt. De fleste af passagererne i den foreste del af det øverste dæk overlevede, ligesom dem, der var nær fronten på det nedre dæk, gjorde, inkl. chaufføren; men de, der var i bussens bagende, blev mere alvorligt såret. Omfanget af skader på ofrenes kroppe resulterede i en længerevarende forsinkelse i annoncering af dødstallet fra bombningen, mens politiet fik klarlagt, hvor mange lig der var til stedet, og om bombemanden var en af dem. Adskillige forbipasserende blev også såret af eksplosionen, og bygningerne omkring eksplosionen blev beskadiget af vragdele.

Den bombaderede bus blev efterfølgende dækket med en presenning og fjernes på en blokvogn for kriminaltekniske undersøgelser på et hemmeligt sted hos Forsvarsministeriet. Køretøjen blev til sidst afleveret til Stagecoach og efterfølgened ophugget 15. oktober 2009. En erstatningsbus, en ny Alexander Dennis Enviro400 (flådenr. 18500, der sidenhen er ændret til 19000, registreringsnummer LX55 HGC), blev navngivet "Spirit of London". I oktober 2012 blev "Spirit of London"-bussen sat i brand under et brandangreb.[7] Den blev repareret og renoveret for £60.000 og blev genindsat i drift i april 2013.[8] To 14-årige piger blev sigtet for angrebet.[7]

Ofre

[redigér | rediger kildetekst]| Land | Antal |

|---|---|

| 32 | |

| 3 | |

| 2 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| 1 | |

| Total | 52 |

De 52 ofre havde alsidig baggrunde. Blandt dem var der adskillige udenlandsk fødte britiske statsborgere, udenlandske udvekslingsstudenter, forældre og et britiske par gennem 14 år. Hovedparten af ofrene boede i eller nær London. På grund af forsinkelser på togene før angrebet og de efterfølgende trafikproblemer, som de forårsagede, omkom adskillige ofre ombord på tog og busser, som de ikke normalt ville have taget. Ofrenes alder varierede fra 20 til 60 år og gennemsnitsalderen var 34.

Alle ofrene boede i Storbritannien. 32 af dem var britiske. Et offer kom fra hver af Afghanistan, Frankrig, Ghana, Grenada, Indien, Iran, Israel, Italien, Kenya, Mauritius, New Zealand, Nigeria, Rumænien, Sri Lanka og Tyrkiet. Tre ofre var polske statsborgere, mens et offer havde dobbelt australsk-vietnamesisk statsborgerskab og en havde dobbelt amerikansk-vietnamesisk statsborgerskab.[9]

Syv omkom ved Aldgate, seks ved Edgware Road, 26 ved Russell Square (heriblandt det britiske par) og 13 ved Tavistock Square.

Bombemænd

[redigér | rediger kildetekst]Profiler

[redigér | rediger kildetekst]De fire selvmordsbombemænd blev senere identificeret og navngivet:

- Mohammad Sidique Khan: 30 år. Khan detonerede sin bombe lige efter at have kørt fra Edgware Road Station på et tog på vej mod Paddington, kl 08:50. Han boede i Beeston, Leeds, med sin kone og barn, hvor han arbejdede som en mentor på en grundskole. Eksplosionen dræbte syv personer, inkl. Khan selv.

- Shehzad Tanweer: 22 år. Han detonerede en bombe ombord på et tog, der kørte mellem Liverpool Street Station og Aldgate Station, kl. 08:50. Han boede i Leeds med sin mor og far, og han arbejdede i en fish and chips-butik. Otte personer, inkl. Tanweer, blev dræbt af eksplosionen.

- Germaine Lindsay: 19 år. Han detonerede sin bombe på et tog, der kørte mellem King's Cross og Russell Square Stationer, kl. 08:50. Han boede i Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, med sin gravide kone og søn. Hans eksplosion dræbte 27 personer, inkl. Lindsay selv.

- Hasib Hussain: den yngste af de fire med sine 18 år. Hussain detonerede sin bombe på det øverste dæk af en dobbeltdækkerbus kl. 09:47. Han boede i Leeds med sin bror og svigerinde. 14 personer, inkl. Hussain, døede i eksplosionen på Tavistock Square.

Tre af bombemændene var britisk fødte sønner af pakistanske immigranter. Lindsay var konvertit, født i Jamaica.

Charles Clarke, der var Home Secretary under angrebet, beskrev bombemændene som "cleanskins", et begreb der beskriver dem som hidtil ukendte hos myndigheder før de udførte deres angreb.[10] På dagen for angrebene havde alle fire rejst til Luton, Bedfordshire, i bil og derfra til London med tog. De blev optaget med videoovervågning, da de ankom til King's Cross Station omkring kl. 08:30.

12. juli 2005 rapporterede BBC, at antiterrorchefen hos Metropolitan Police Service, Peter Clarke havde udtalt, at en af bombemændenes ejendele var blevet fundet ved både Aldgate- og Edgware Road-eksplosionerne.

Videotaped statements

[redigér | rediger kildetekst]Two of the bombers made videotapes describing their reasons for becoming what they called "soldiers". In a videotape broadcast by Al Jazeera on 1 September 2005, Mohammad Sidique Khan, described his motivation. The tape had been edited and also featured al-Qaeda member—and future leader—Ayman al-Zawahiri:[11]

I and thousands like me are forsaking everything for what we believe. Our drive and motivation doesn't come from tangible commodities that this world has to offer. Our religion is Islam, obedience to the one true God and following the footsteps of the final prophet messenger. Your democratically-elected governments continuously perpetuate atrocities against my people all over the world. And your support of them makes you directly responsible, just as I am directly responsible for protecting and avenging my Muslim brothers and sisters. Until we feel security you will be our targets and until you stop the bombing, gassing, imprisonment and torture of my people we will not stop this fight. We are at war and I am a soldier. Now you too will taste the reality of this situation.

A second part of the tape continues

...I myself, I myself, I make dua (pray) to Allah ... to raise me amongst those whom I love like the prophets, the messengers, the martyrs and today's heroes like our beloved Sheikh Osama Bin Laden, Dr Ayman al-Zawahri and Abu Musab al-Zarqawi and all the other brothers and sisters that are fighting in the ... of this cause.

On 6 July 2006, a videotaped statement by Shehzad Tanweer was broadcast by Al-Jazeera. In the video, which may have been edited[12] to include remarks by al-Zawahiri who appeared in Khan's video, Tanweer said:

What have you witnessed now is only the beginning of a string of attacks that will continue and become stronger until you pull your forces out of Afghanistan and Iraq. And until you stop your financial and military support to America and Israel.

Tanweer argued that the non-Muslims of Britain deserve such attacks because they voted for a government which "continues to oppress our mothers, children, brothers and sisters in Palestine, Afghanistan, Iraq and Chechnya."[13]

Effects and response

[redigér | rediger kildetekst]

Initial reports

[redigér | rediger kildetekst]Initial reports suggested that a power surge on the Underground power grid had caused explosions in power circuits. This was later ruled out by power suppliers National Grid. Commentators suggested that the explanation had been made because of bomb damage to power lines along the tracks; the rapid series of power failures caused by the explosions (or power being ended by means of switches at the locations to permit evacuation) looked similar, from the point of view of a control room operator, to a cascading series of circuit breaker operations that would result from a major power surge. A couple of hours after the bombings, Home Secretary Charles Clarke confirmed the incidents were terrorist attacks.[14]

Security alerts

[redigér | rediger kildetekst]Although there were security alerts at many locations throughout the United Kingdom, no other terrorist incidents occurred outside central London. Suspicious packages were destroyed in controlled explosions in Edinburgh, Brighton, Coventry, Southampton, Portsmouth, Darlington and Nottingham. Security across the country was increased to the highest alert level.

The Times reported on 17 July 2005 that police sniper units were following as many as a dozen al-Qaeda suspects in Britain. The covert armed teams were ordered to shoot to kill if surveillance suggested that a terror suspect was carrying a bomb and he refused to surrender if challenged. A member of the Metropolitan Police's Specialist Firearms Command said: "These units are trained to deal with any eventuality. Since the London bombs they have been deployed to look at certain people."[15]

Transport and telecoms disruption

[redigér | rediger kildetekst]Vodafone reported that its mobile telephone network reached capacity at about 10am on the day of the bombings, and it was forced to initiate emergency procedures to prioritise emergency calls (ACCOLC, the 'access overload control'). Other mobile phone networks also reported failures. The BBC speculated that the telephone system was shut down by security services to prevent the possibility of mobile phones being used to trigger bombs. Although this option was considered, it became clear later that the intermittent unavailability of both mobile and landline telephone systems was due only to excessive usage. ACCOLC was activated only in a 1 km (0,6 mi) radius around Aldgate Tube Station because key emergency personnel did not have ACCOLC-enabled mobile phones.[16] The communications failures during the emergency sparked discussions to improve London's emergency communications system.[17]

For most of the day, central London's public transport system was largely out of service following the complete closure of the Underground, the closure of the Zone 1 bus network, and the evacuation of incident sites such as Russell Square. Bus services restarted at 4pm on 7 July, and most mainline railway stations resumed service soon afterward. River vessels were pressed into service to provide a free alternative to overcrowded trains and buses. Local lifeboats were required to act as safety boats, including the Sheerness lifeboat from the Isle of Sheppey in Kent. Thousands of people chose to walk home or to the nearest Zone 2 bus or railway station. Most of the Underground, apart from the stations affected by the bombs, resumed service the next morning, though some commuters chose to stay at home.

Much of King's Cross railway station was also closed, with the ticket hall and waiting area being used as a makeshift hospital to treat casualties. Although the station reopened later during the day, only suburban rail services were able to use it, with Great North Eastern Railway trains terminating at Peterborough (the service was fully restored on 9 July). King's Cross St. Pancras tube station remained available only to Metropolitan line services to facilitate the ongoing recovery and investigation for a week, though Victoria line services were restored on 15 July and the Northern line on 18 July. St. Pancras station, located next to King's Cross, was shut on the afternoon of the attacks, with all Midland Mainline trains terminating at Leicester, causing disruption to services to Sheffield, Nottingham and Derby.

By 25 July there were still disruptions to the Piccadilly line (which was not running between Arnos Grove and Hyde Park Corner in either direction), the Hammersmith & City line (which was only running a shuttle service between Hammersmith and Paddington) and the Circle line (which was suspended in its entirety). The Metropolitan line resumed services between Moorgate and Aldgate on 25 July. The Hammersmith & City line was also operating a peak-hours service between Whitechapel and Baker Street. Most of the remainder of the Underground network was however operating normally.

On 2 August the Hammersmith & City line resumed normal service; the Circle line was still suspended, though all Circle line stations are also served by other lines. The Piccadilly line service resumed on 4 August.

Economic effect

[redigér | rediger kildetekst]

There were limited reactions to the attack in the world economy as measured by financial market and exchange rate activity. The value of the British pound decreased 0.89 cents to a 19-month low against the US dollar. The FTSE 100 Index fell by about 200 points during the two hours after the first attack. This was its greatest decrease since the invasion of Iraq, and it triggered the London Stock Exchange's 'Special Measures', restricting panic selling and aimed at ensuring market stability. By the time the market closed it had recovered to only 71.3 points (1.36%) down on the previous day's three-year closing high. Markets in France, Germany, the Netherlands and Spain also closed about 1% down on the day.

US market indexes increased slightly, partly because the dollar index increased sharply against the pound and the euro. The Dow Jones Industrial Average gained 31.61 to 10,302.29. The NASDAQ Composite Index increased 7.01 to 2075.66. The S&P 500 increased 2.93 points to 1197.87 after decreasing as much as 1%. Every benchmark value gained 0.3%.[18]

The market values increased again on 8 July as it became clear that the damage caused by the bombings was not as great as thought initially. By end of trading the market had recovered fully to above its level at start of trading on 7 July. Insurers in the UK tend to reinsure their terrorist liabilities in excess of the first £75,000,000 with Pool Re, a mutual insurer established by the government with major insurers. Pool Re has substantial reserves and newspaper reports indicated that claims would easily be funded.

On 9 July, the Bank of England, HM Treasury and the Financial Services Authority revealed that they had instigated contingency plans immediately after the attacks to ensure that the UK financial markets could keep trading. This involved the activation of a "secret chatroom" on the British government's Financial Sector Continuity website, which allowed the institutions to communicate with the country's banks and market dealers.[19]

Media response

[redigér | rediger kildetekst]

Continuous news coverage of the attacks was broadcast throughout 7 July, by both BBC One and ITV1, uninterrupted until 7 p.m. Sky News did not broadcast any advertisements for 24 hours. ITN confirmed later that its coverage on ITV1 was its longest uninterrupted on-air broadcast of its 50-year history. Television coverage was notable for the use of mobile telephone footage sent in by members of the public and live pictures from traffic CCTV cameras.

The BBC Online website recorded an all-time bandwidth peak of 11 Gb/s at midday on 7 July. BBC News received some 1 billion total accesses throughout the course of the day (including all images, text and HTML), serving some 5.5 terabytes of data. At peak times during the day there were 40,000-page requests per second for the BBC News website. The previous day's announcement of the 2012 Summer Olympics being awarded to London resulted in up to 5 Gb/s. The previous all time maximum for the website followed the announcement of the Michael Jackson verdict, which used 7.2 Gb/s.[20]

On 12 July it was reported that the British National Party released leaflets showing images of the 'No. 30 bus' after it was destroyed. The slogan, "Maybe now it's time to start listening to the BNP" was printed beside the photo. Home Secretary Charles Clarke described it as an attempt by the BNP to "cynically exploit the current tragic events in London to further their spread of hatred".[21]

Some media outside the UK complained that successive British governments had been unduly tolerant towards radical Islamist militants, so long as they were involved in activities outside the UK.[22] Britain's claimed reluctance to extradite or prosecute terrorist suspects resulted in London being dubbed Londonistan by the columnist Melanie Phillips (a term similar to that used by American anti-Semites referring to 'Jew York').[23]

Claims of responsibility

[redigér | rediger kildetekst]Even before the identity of the bombers became known, former Metropolitan Police commissioner Lord Stevens said he believed they were almost certainly born or based in Britain, and would not "fit the caricature al-Qaeda fanatic from some backward village in Algeria or Afghanistan".[24] The attacks would have required extensive preparation and prior reconnaissance efforts, and a familiarity with bomb-making and the London transport network as well as access to significant amounts of bomb-making equipment and chemicals.

Some newspaper editorials in Iran blamed the bombing on British or American authorities seeking to further justify the War on Terror, and claimed that the plan that included the bombings also involved increasing harassment of Muslims in Europe.[25]

On 13 August 2005, quoting police and MI5 sources, The Independent reported that the bombers acted independently of an al-Qaeda terror mastermind some place abroad.[26]

On 1 September it was reported that al-Qaeda officially claimed responsibility for the attacks in a videotape broadcast by the Arab television network Al Jazeera. However, an official inquiry by the British government reported that the tape claiming responsibility had been edited after the attacks, and that the bombers did not have direct assistance from al-Qaeda.[27] Zabi uk-Taifi, an al-Qaeda commander arrested in Pakistan in January 2009, may have had connections to the bombings, according to Pakistani intelligence sources.[28] More recently, documents found by German authorities on a terrorist suspect arrested in Berlin in May 2011 have suggested that Rashid Rauf, a British al Qaeda operative, played a key role in planning the attacks.[29]

Abu Hafs al-Masri Brigades

[redigér | rediger kildetekst]A second claim of responsibility was posted on the Internet by another al-Qaeda-linked group, Abu Hafs al-Masri Brigades. The group had, however, previously falsely claimed responsibility for events that were the result of technical problems, such as the 2003 London blackout and the US Northeast blackout of 2003.[30]

Conspiracy theories

[redigér | rediger kildetekst]

A survey of 500 British Muslims undertaken by Channel 4 News in 2007 found that 24% believed the four bombers blamed for the attacks did not perform them.[31] In 2006, the government had refused to hold a public inquiry, stating that "it would be a ludicrous diversion". Prime Minister Tony Blair said an independent inquiry would "undermine support" for MI5, while the leader of the opposition, David Cameron, said only a full inquiry would "get to the truth".[32] In reaction to revelations about the extent of security service investigations into the bombers prior to the attack, the Shadow Home Secretary, David Davis, said: "It is becoming more and more clear that the story presented to the public and Parliament is at odds with the facts."[33] However, the decision against an independent public inquest was later reversed. A full public inquest into the bombings was subsequently begun from October 2010. Coroner Lady Justice Hallett stated that the inquest would examine how each victim died and whether MI5, if it had worked better, could have prevented the attack.[34]

There have been various conspiracy theories proposed about the bombings, including the suggestion that the bombers were 'patsies', based on claims about timings of the trains and the train from Luton, supposed explosions underneath the carriages, and allegations of the faking of the one time-stamped and dated photograph of the bombers at Luton station.[35][36] Claims made by one theorist in the Internet video 7/7 Ripple Effect were examined by the BBC documentary series The Conspiracy Files, in an episode titled "7/7" first broadcast on 30 June 2009, which debunked many of the video's claims.[37]

On the day of the bombings Peter Power of Visor Consultants gave interviews on BBC Radio 5 Live and ITV saying that he was working on a crisis management simulation drill, in the City of London, "based on simultaneous bombs going off precisely at the railway stations where it happened this morning", when he heard that an attack was going on in real life. He described this as a coincidence. He also gave an interview to the Manchester Evening News where he spoke of "an exercise involving mock broadcasts when it happened for real".[38] After a few days he dismissed it as a "spooky coincidence" on Canadian TV.[39]

Investigation

[redigér | rediger kildetekst]Initial results

[redigér | rediger kildetekst]| Number of fatalities | |

|---|---|

| Aldgate | 7 |

| Edgware Road | 6 |

| King's Cross | 26 |

| Tavistock Square | 13 |

| Total number of fatal victims | 52 |

| Suicide bombers | 4 |

| Total fatalities | 56 |

Initially, there was much confused information from police sources as to the origin, method, and even timings of the explosions. Forensic examiners had thought initially that military-grade plastic explosives were used, and, as the blasts were thought to have been simultaneous, that synchronised timed detonators were employed. This hypothesis changed as more information became available. Home-made organic peroxide-based devices were used, according to a May 2006 report from the British government's Intelligence and Security Committee.[40] The explosive was triacetone triperoxide.[41]

Fifty-six people, including the four suicide bombers, were killed by the attacks[42] and about 700 were injured, of whom about 100 were hospitalised for at least one night. The incident was the deadliest single act of terrorism in the United Kingdom since the 1988 bombing of Pan Am Flight 103, which crashed on Lockerbie and killed 270 people, and the deadliest bombing in London since the Second World War.[43]

Police examined about 2,500 items of CCTV footage and forensic evidence from the scenes of the attacks. The bombs were probably placed on the floors of the trains and bus.

Investigators identified four men who they alleged had been the suicide bombers. This made the bombings the first ever suicide attack in the British Isles.[44] Nicolas Sarkozy, the interior minister and future President of France, caused consternation at the British Home Office when he briefed the press that one of the names had been described the previous year at an Anglo-French security meeting as an asset of British intelligence. Home Secretary Charles Clarke said later that this was "not his recollection."

Vincent Cannistraro, former head of the Central Intelligence Agency's anti-terrorism centre, told The Guardian that "two unexploded bombs" were recovered as well as "mechanical timing devices", although this claim was explicitly rejected by London's Metropolitan Police Service.[45]

Police raids

[redigér | rediger kildetekst]West Yorkshire Police raided six properties in the Leeds area on 12 July: two houses in Beeston, two in Thornhill, one in Holbeck and one in Alexandra Grove in Hyde Park, Leeds. One man was arrested. Officers also raided a residential property on Northern Road in the Buckinghamshire town of Aylesbury on 13 July.

The police service say a significant amount of explosive material was found in the Leeds raids and a controlled explosion was carried out at one of the properties. Explosives were also found in the vehicle associated with one of the bombers, Shehzad Tanweer, at Luton railway station and subjected to controlled explosion.[6][46][47][48]

Luton cell

[redigér | rediger kildetekst]There was speculation about a possible association between the bombers and another alleged Islamist cell in Luton which was ended during August 2004. The Luton group was uncovered after Muhammad Naeem Noor Khan was arrested in Lahore, Pakistan. His laptop computer was said to contain plans for tube attacks in London, as well as attacks on financial buildings in New York City and Washington, D.C. The group was subject to surveillance but on 2 August 2004 The New York Times published Khan's name, citing Pakistani sources. The news leak forced police in Britain and Canada to make arrests before their investigations were complete. The US government later said they had given the name to some journalists as "background information", for which Tom Ridge, the United States Secretary of Homeland Security, apologised.

When the Luton cell was ended, one of the London bombers, Mohammad Sidique Khan (no known relation), was scrutinised briefly by MI5 who determined that he was not a likely threat and he was not surveilled.[49]

March 2007 arrests

[redigér | rediger kildetekst]On 22 March 2007, three men were arrested in connection with the bombings. Two were arrested at 1 pm at Manchester Airport, attempting to board a flight bound for Pakistan that afternoon. They were apprehended by undercover officers who had been following the men as part of a surveillance operation. They had not intended to arrest the men that day, but believed they could not risk letting the suspects leave the country. A third man was arrested in the Beeston area of Leeds at an address on the street where one of the suicide bombers had lived before the attacks.[50]

May 2007 arrests

[redigér | rediger kildetekst]On 9 May 2007 police made four further arrests, three in Yorkshire and one in Selly Oak, Birmingham. Hasina Patel, widow of the presumed ringleader Mohammed Sidique Khan, was among those arrested for "commissioning, preparing or instigating acts of terrorism".[51]

Three of those arrested, including Patel, were released on 15 May.[51] The fourth, Khalid Khaliq, an unemployed single father of three, was charged on 17 July 2007 with possessing an al-Qaeda training manual, but the charge was not related to the 2005 London attacks. Conviction for possession of a document containing information likely to be useful to a person committing or preparing an act of terrorism carried a maximum ten-year jail sentence.[52]

Deportation of Abdullah el-Faisal

[redigér | rediger kildetekst]Abdullah el-Faisal was deported to Jamaica, his country of origin, from Britain on 25 May 2006 after reaching the parole date in his prison sentence. He was found guilty of three charges of soliciting the murder of Jews, Americans and Hindus and two charges of using threatening words to incite racial hatred in 2003 and, despite an appeal, was sentenced to seven years imprisonment. In 2006 John Reid alleged to MPs that el-Faisal had influenced Jamaican-born Briton Germaine Lindsay into participating in the 7/7 bombings.[53][54]

Investigation of Mohammad Sidique Khan

[redigér | rediger kildetekst]The Guardian reported on 3 May 2007 that police had investigated Mohammad Sidique Khan twice during 2005. The newspaper said it "learned that on 27 January 2005, police took a statement from the manager of a garage in Leeds which had loaned Khan a courtesy car while his vehicle was being repaired." It also said that "on the afternoon of 3 February an officer from Scotland Yard's anti-terrorism branch carried out inquiries with the company which had insured a car in which Khan was seen driving almost a year earlier". Nothing about these inquiries appeared in the report by Parliament's intelligence and security committee after it investigated the 7 July attacks. Scotland Yard described the 2005 inquiries as "routine", while security sources said they were related to the fertiliser bomb plot.

Reports of warnings

[redigér | rediger kildetekst]While no warnings before the 7 July bombings have been documented officially or acknowledged, the following are sometimes quoted as indications either of the events to come or of some foreknowledge.

- One of the London bombers, Mohammad Sidique Khan, was briefly scrutinised by MI5 who determined that he was not a likely threat and he was not put under surveillance.[55]

- Some news stories, current a few hours after the attacks, questioned the British government's contention that there had not been any warning or prior intelligence. It was reported by CBS News that a senior Israeli official said that British police told the Israeli embassy in London minutes before the explosions that they had received warnings of possible terror attacks in the UK capital. An AP report used by a number of news sites, including The Guardian, attributed the initial report of a warning to an Israeli "Foreign Ministry official, speaking on condition of anonymity", but added Foreign Minister Silvan Shalom's later denial on Israel Defense Forces Radio: "There was no early information about terrorist attacks." A similar report on the site of right-wing Israeli paper Israel National News/Arutz Sheva attributed the story to "Army Radio quoting unconfirmed reliable sources."[56] Although the report has been retracted, the original stories are still circulated as a result of their presence on the news websites' archives.

- In an interview with the Portuguese newspaper Público a month after the 2004 Madrid train bombings, Syrian-born cleric Omar Bakri Muhammad warned that "a very well-organised" London-based group which he called "al-Qaeda Europe" was "on the verge of launching a big operation."[57] In December 2004, Bakri vowed that, if Western governments did not change their policies, Muslims would give them "a 9/11, day after day after day."[22]

- According to a 17 November 2004 post on the Newsweek website, US authorities in 2004 had evidence that terrorists were planning a possible attack in London. In addition, the article stated that, "fears of terror attacks have prompted FBI agents based in the U.S. embassy in London to avoid travelling on London's popular underground railway (or tube) system."[58]

- In an interview published by the German magazine Bild am Sonntag dated 10 July 2005, Meir Dagan, director of the Israeli intelligence agency Mossad, said that the agency's office in London was alerted to the impending attack at 8:43 am, six minutes before the first bomb detonated. The warning of a possible attack was a result of an investigation into an earlier terrorist bombing in Tel Aviv, which may have been related to the London bombings.[59]

Anwar al-Awlaki

[redigér | rediger kildetekst]The Daily Telegraph reported that radical imam Anwar al-Awlaki inspired the bombers.[60] The bombers transcribed lectures of al-Awlaki while plotting the bombings. His materials were found in the possession of accused accomplices of the suicide bombers. Awlaki has also been linked to the 2006 Ontario terrorism plot in Canada, the 2007 Fort Dix attack plot in New Jersey, the 2009 Fort Hood shooting in Texas, and the failed attack on Northwest Airlines Flight 253, a commercial flight from Amsterdam to Detroit, on Christmas Day, 2009.[61] Al-Awlaki was killed by a US drone attack in 2011.

Independent inquest

[redigér | rediger kildetekst]In October 2010 an independent coroner's inquest of the bombings began.[62] Lady Justice Hallett was appointed to hear the inquest, which would consider both whether the attacks were preventable, and the emergency service response to them.

After seven months of evidence and deliberation, the verdict of the inquiry was released and read in the Houses of Parliament on 9 May 2011. It determined that the 52 victims had been unlawfully killed; their deaths could not have been prevented, and they would probably have died "whatever time the emergency services reached and rescued them". Hallett concluded that MI5 had not made every possible improvement since the attacks but that it was not "right or fair" to say more attention should have been paid to ringleader Mohammad Sidique Khan prior to 7 July. She also decided that there should be no public inquiry.[63][64]

The report provided nine recommendations to various bodies:[65]

- With reference to a photograph of Khan and Shehzad Tanweer which was so badly cropped by MI5 that the pair was virtually unrecognisable to the US authorities asked to review it, the inquiry recommended that procedures be improved so that humans asked to view photographs are shown them in best possible quality.

- In relation to the suggestion that MI5 failed to realise the suspects were important quickly enough, the inquiry recommended that MI5 improves the way it records decisions relating to suspect assessment.

- The inquiry recommended that 'major incident' training for all frontline staff, especially those working on the Underground, is reviewed.

- With regards to the facts that London Underground (LU) is unable to declare a 'major incident' itself and that LU was not invited to an emergency meeting at Scotland Yard at 10:30 am on the morning of the bombings, the inquiry recommends that the way Transport for London (TfL) and the London resilience team are alerted to major incidents and the way the emergency services are informed is reviewed.

- Regarding the confusion on 7 July 2005 over the emergency rendezvous point, it was recommended that a common initial rendezvous point is permanently staffed and advised to emergency services;

- In response to the evidence that some firefighters refused to walk on the tracks at Aldgate to reach the bombed train because they had not received confirmation that the electric current had been switched off, the inquiry recommended a review into how emergency workers confirm whether the current is off after a major incident.

- A recommendation was made that TfL reviewed the provision of stretchers and first aid equipment at Underground stations.

- Training of London Ambulance Service (LAS) staff of "multi-casualty triage" should be reviewed, following concerns in the inquest that some casualties were not actually treated by paramedics who had triaged them.

- A final recommendation was made to the Department of Health, the Mayor of London and the London resilience team to review the capability and funding of emergency medical care in the city.

Newspaper phone hacking

[redigér | rediger kildetekst]It was revealed in July 2011 that relatives of some of the victims of the bombings may have had their telephones accessed by the News of the World in the aftermath of the attacks. The revelations added to an existing controversy over phone hacking by the tabloid newspaper.

The fathers of two victims, one in the Edgware Road blast and another at Russell Square, told the BBC that police officers investigating the alleged hacking had warned them that their contact details were found on a target list, while a former firefighter who helped injured passengers escape from Edgware Road also said he had been contacted by police who were looking into the hacking allegations.[66] A number of survivors from the bombed trains also revealed that police had warned them their phones may have been accessed and their messages intercepted, and in some cases officers advised them to change security codes and PIN numbers.[67][68][69]

Memorials

[redigér | rediger kildetekst]

Since the bombings, the United Kingdom and other nations have honoured the victims in several ways. Most of these memorials have included moments of silence, candlelit vigils, and the laying of flowers at the attack sites. Foreign leaders have also remembered the dead by ordering their flags to be flown at half-mast, signing books of condolences at embassies of the UK, and issuing messages of support and condolences to the British people.

United Kingdom

[redigér | rediger kildetekst]The government ordered the Union Flag to be flown at half-mast on 8 July.[70] The following day, the Bishop of London led prayers for the victims during a service paying tribute to the role of women during the Second World War. A vigil, called by the Stop the War Coalition, Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and Muslim Association of Britain, was held from 5 pm, at Friends Meeting House on Euston Road.

A two-minute silence was held on 14 July 2005 throughout Europe.[71] Thousands attended a vigil at 6 pm on Trafalgar Square. After an initial silence there was a series of speakers for two hours. A memorial service was held at St Paul's Cathedral on 1 November 2005.[72] To mark the first anniversary of the attack, a two-minute silence was observed at midday across the country.[73]

A permanent memorial was unveiled in 2009 by Prince Charles in Hyde Park to mark the fourth anniversary of the bombings.[74] On the eve of the ninth anniversary of the attacks in 2014 the memorial was defaced with messages including "Blair lied, thousands died". The graffiti was removed within hours.[75]

During the opening ceremony of the 2012 Olympic Games in London a minute's silence was held to commemorate those killed in the attacks.

International

[redigér | rediger kildetekst]US President George W. Bush visited the British embassy the day after the bombings, upon his return from the G8 summit in Scotland, and signed a book of condolence.[76] In Washington, D.C., the US Army band played "God Save the Queen" (the British national anthem, the melody of which is also used in an American patriotic hymn, "My Country, 'Tis of Thee"), a suggestion that US Army veteran John Miska made to Vice Chief of Staff General Cody, outside the British embassy in the city.[77] On 12 July, a Detroit Symphony Orchestra brass ensemble played the British national anthem during the pre-game festivities of the Major League Baseball All-Star Game at Comerica Park in Detroit.[78]

Flags were ordered to fly at half-mast across Australia, New Zealand[79] and Canada.[80] The Union Flag was raised to half-mast alongside the Flag of Australia on Sydney Harbour Bridge as a show of "sympathy between nations".[81]

Moments of silence were observed in the European Parliament, the Polish parliament and by the Irish government[82] on 14 July. The British national anthem was played at the changing of the royal guard at Plaza de Oriente in Madrid in memorial to the victims of the attacks. The ceremony was attended by the British ambassador to Spain and members of the Spanish Royal Family. After the 2004 Madrid train bombings, the UK had hosted a similar ceremony at Buckingham Palace.[83]

See also

[redigér | rediger kildetekst]- 2007 London car bombs

- Death of Jean Charles de Menezes

- Murder of Lee Rigby

- September 11 attacks

- 2004 Madrid train bombings

- November 2015 Paris attacks

- December 2015 London Underground attack

- 2016 Brussels bombings

References

[redigér | rediger kildetekst]- ^ Goodhart, David. The British Dream. Atlantic Books, London (2013): p. 222

- ^ "I'm lucky to be here, says driver". BBC. 11 juli 2005. Arkiveret fra originalen 10 november 2006. Hentet 12 november 2006.

{{cite news}}: Ugyldig|deadurl=no(hjælp); Ukendt parameter|deadurl=ignoreret (|url-status=foreslået) (hjælp)CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ North, Rachel (15 juli 2005). "Coming together as a city". BBC. Hentet 12 november 2006.

{{cite news}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ "Tube log shows initial confusion". BBC News. 12 juli 2005. Hentet 12 november 2006.

{{cite news}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ "Indepth London Attacks". BBC News. Hentet 17 oktober 2009.

{{cite news}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ a b Campbell, Duncan; Laville, Sandra (13 juli 2005). "British suicide bombers carried out London attacks, say police". The Guardian. Hentet 15 november 2006.

{{cite news}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ a b "Suspected arson on 7/7 tribute bus 'Spirit of London'". BBC News. 20 oktober 2012. Hentet 25 marts 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ "Stagecoach relaunches 'Spirit of London' bus following arson attack - Stagecoach Group". stagecoach.com.

- ^ "The 52 victims of the 7/7 bombings remembered" (britisk engelsk). 2015-07-06. Hentet 2016-08-25.

- ^ Lewis, Leo (6 maj 2007). "The jihadi house parties of hate: Britain's terror network offered an easy target the security sevices [sic] missed, says Shiv Malik". The Times. Arkiveret fra originalen den 3 august 2010. Hentet 2 august 2010.

And how could Charles Clarke, home secretary at the time, claim that Khan and his associates were "clean skins" unknown to the security services?

{{cite news}}: Ukendt parameter|deadurl=ignoreret (|url-status=foreslået) (hjælp)CS1-vedligeholdelse: BOT: original-url status ukendt (link) CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ London bomber: Text in full, BBC, 1 September 2005. Retrieved 14 October 2010.

- ^ "Video of London bomber released". Guardian. 8 juli 2006.

{{cite news}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ Video of London suicide bomber released, The Times, 6 July 2006. Retrieved 3 March 2007; a transcript of the tape is "available at Wikisource". Arkiveret fra originalen 13 oktober 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ "Incidents in London". United Kingdom Parliament. Hentet 30 juli 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ Lewis, Leo (17 juli 2005). "Police snipers track al-Qaeda suspects". The Times Online. London. Arkiveret fra originalen 22 oktober 2006. Hentet 3 december 2006.

{{cite news}}: Ugyldig|deadurl=yes(hjælp); Ukendt parameter|deadurl=ignoreret (|url-status=foreslået) (hjælp)CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ McCue, Andy. "7/7 bomb rescue efforts hampered by communication failings". ZDNet UK. Hentet 18 april 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ "London Assembly 7 July Review Committee, follow-up re port" (PDF). London Assembly. Hentet 18 april 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ Lawrence, Dune (7 juli 2005). "U.S. Stocks Rise, Erasing Losses on London Bombings; Gap Rises". Bloomberg L.P. Hentet 3 december 2006.

{{cite news}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ "Banks talked via secret chatroom". BBC News. 8 juli 2005. Hentet 3 december 2006.

{{cite news}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ "Statistics on BBC Webservers 7 July 2005". BBC Online. Arkiveret fra originalen 3 juli 2007. Hentet 3 december 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ "Politics BNP campaign uses bus bomb photo". BBC News. 12 juli 2005. Arkiveret fra originalen 26 oktober 2009. Hentet 17 oktober 2009.

{{cite news}}: Ugyldig|deadurl=no(hjælp); Ukendt parameter|deadurl=ignoreret (|url-status=foreslået) (hjælp)CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ a b Sciolino, Elaine; van Natta, Jr., Don (10 juli 2005). "For a Decade, London Thrived as a Busy Crossroads of Terror". The New York Times. Hentet 8 juli 2008.

{{cite news}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ Philips, Melanie. Londonistan. Encounter Books, 2006, p. 189 ff.

- ^ "Police appeal for bombing footage". BBC News. 10 juli 2005. Arkiveret fra originalen 23 november 2006. Hentet 3 december 2006.

{{cite news}}: Ugyldig|deadurl=no(hjælp); Ukendt parameter|deadurl=ignoreret (|url-status=foreslået) (hjælp)CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ Harrison, Frances (11 juli 2005). "Iran press blames West for blasts". BBC News. Arkiveret fra originalen 20 november 2006. Hentet 3 december 2006.

{{cite news}}: Ugyldig|deadurl=no(hjælp); Ukendt parameter|deadurl=ignoreret (|url-status=foreslået) (hjælp)CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ Bennetto, Jason; Ian Herbert (13 august 2005). "London bombings: the truth emerges". The Independent. Hentet 3 december 2006.

{{cite news}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ Townsend, Mark (9 april 2006). "Leak reveals official story of London bombings UK news The Observer". Guardian. Hentet 17 oktober 2009.

{{cite news}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ Nelson, Dean; Khan, Emal (22 januar 2009). "Al-Qaeda commander linked to 2005 London bombings led attacks on Nato convoys". The Telegraph. Arkiveret fra originalen 30 januar 2009. Hentet 5 februar 2009.

{{cite news}}: Ugyldig|deadurl=no(hjælp); Ukendt parameter|deadurl=ignoreret (|url-status=foreslået) (hjælp)CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ Robertson, Nic Cruickshank, Paul and Lister, Tim (30 April 2012) "Documents give new details on al Qaeda's London bombings" CNN.com

- ^ Johnston, Chris (9 juli 2005). "Tube blasts "almost simultaneous"". The Guardian. London. Hentet 3 december 2006.

{{cite news}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ Soni, Darshna (4 juni 2007). "Survey: 'government hasn't told truth about 7/7'". Channel 4 News. Hentet 12 august 2009.

{{cite news}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ Carter, Helen; Dodd, Vikram; Cobain, Ian (3 maj 2007). "7/7 leader: more evidence reveals what police knew". The Guardian. London. Hentet 17 oktober 2009.

{{cite news}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ Dodd, Vikram (3 maj 2007). "7/7 leader: more evidence reveals what police knew". The Guardian. London. Hentet 20 december 2007.

{{cite news}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ "7/7 bombs acts of 'merciless savagery', inquests told". BBC News. 11 oktober 2010. Hentet 15 maj 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ Honingsbaum, Mark (27 juni 2006). "Seeing isn't believing". The Guardian. Hentet 12 august 2009.

{{cite news}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ Soni, Darshna (4 juni 2007). "7/7: the conspiracy theories". Channel 4 News. Hentet 12 august 2009.

{{cite news}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ "Unmasking the mysterious 7/7 conspiracy theorist". BBC News Magazine. 30 juni 2009. Arkiveret fra originalen 6 juli 2009. Hentet 12 august 2009.

{{cite news}}: Ugyldig|deadurl=no(hjælp); Ukendt parameter|deadurl=ignoreret (|url-status=foreslået) (hjælp)CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ Manchester Evening News "King's Cross Man's Crisis Course", 8 July 2005

- ^ "BBC4 Coincidence of bomb exercises? 17 July 2005". Arkiveret fra originalen den 14 maj 2007. Hentet 2007-05-14.

{{cite web}}: Ukendt parameter|deadurl=ignoreret (|url-status=foreslået) (hjælp)CS1-vedligeholdelse: BOT: original-url status ukendt (link) CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ Intelligence and Security Committee (maj 2006). "Report into the London Terrorist Attacks on 7 July 2005" (PDF). BBC News. s. 11.

{{cite news}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ Vince, Gaia (15 juli 2005). "Explosives linked to London bombings identified". New Scientist (amerikansk engelsk).

{{cite web}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ "List of the bomb blast victims". BBC News. 20 juli 2005. Hentet 7 juli 2007.

{{cite news}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ Brian Lysaght and Alex Morales (5 juni 2006). "London Bomb Rescuers Were Hindered by Communications". Bloomberg. Hentet 5 august 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ Eggen, Dan; Scott Wilson (17 juli 2005). "Suicide Bombs Potent Tools of Terrorists". The Washington Post. Hentet 3 december 2006.

{{cite news}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ Muir, Hugh; Rosie Cowan (8 juli 2005). "Four bombs in 50 minutes – Britain suffers its worst-ever terror attack". The Guardian. London. Arkiveret fra originalen 17 december 2007. Hentet 3 december 2006.

{{cite news}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ "London bombers "were all British"". BBC News. 12 juli 2005. Hentet 3 december 2006.

{{cite news}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ "One London bomber died in blast". BBC News. 12 juli 2005. Arkiveret fra originalen 16 december 2006. Hentet 3 december 2006.

{{cite news}}: Ugyldig|deadurl=no(hjælp); Ukendt parameter|deadurl=ignoreret (|url-status=foreslået) (hjælp)CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ Bennetto, Jason; Ian Herbert (13 juli 2005). "The suicide bomb plot hatched in Yorkshire". The Independent. London. Hentet 3 december 2006.

{{cite news}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ Leppard, David (17 juli 2005). "MI5 judged bomber "no threat"". The Times Online. London. Hentet 3 december 2006.

{{cite news}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ "Three held over 7 July bombings". BBC News. 22 marts 2007. Arkiveret fra originalen 11 januar 2010. Hentet 1 januar 2010.

{{cite news}}: Ugyldig|deadurl=no(hjælp); Ukendt parameter|deadurl=ignoreret (|url-status=foreslået) (hjælp)CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ a b "Police quiz 7 July bomber's widow". BBC News. 9 maj 2007. Hentet 1 januar 2010.

{{cite news}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ "UK Man bailed over 'al-Qaeda manual'". BBC News. 21 maj 2007. Hentet 17 oktober 2009.

{{cite news}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ "UK Race hate cleric Faisal deported". BBC News. 25 maj 2007. Hentet 17 oktober 2009.

{{cite news}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ "England London , 'Hate preacher' loses his appeal". BBC News. 17 februar 2004. Hentet 17 oktober 2009.

{{cite news}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ MI5 judged bomber "no threat" The Times Online

- ^ Report: Israel was warned ahead of first blast Arutz Sheva – Arkiveret 21 July 2005 hos Wayback Machine

- ^ "Gulf Times". Gulf Times. Arkiveret fra originalen 3 september 2009. Hentet 17 oktober 2009.

{{cite web}}: Ugyldig|deadurl=no(hjælp); Ukendt parameter|deadurl=ignoreret (|url-status=foreslået) (hjælp)CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ Terror Watch: The Real Target? – Newsweek National News – MSNBC.com at www.msnbc.msn.com – Arkiveret 18 November 2004 hos Wayback Machine

- ^ at web.israelinsider.com

- ^ Sherwell, Philip; Gardham, Duncan (23 november 2009). "Fort Hood shooting: radical Islamic preacher also inspired July 7 bombers". The Daily Telegraph. London.

{{cite news}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ Rotella, Sebastian; Meyer, Josh (12 november 2009). "Fort Hood suspect's contact with cleric spelled trouble, experts say". The Los Angeles Times.

{{cite news}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ "Coroner's Inquest into the London bombings of 7 July 2005". 7julyinquests.independent.gov.uk. Hentet 15 juli 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ "7/7 inquest – WMS". Home Office. 9 maj 2011. Hentet 16 september 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ "7/7 inquests: Emergency delays 'did not cause deaths'". BBC News. 6 maj 2011.

{{cite news}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ Owen, Paul (6 maj 2011). "7/7 inquest verdict – Friday 6 May 2011". The Guardian. London.

{{cite news}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ "News of the World 'hacked 7/7 family phones'". BBC News. 6 juli 2011.

{{cite news}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ Hutchinson, Lisa (7 juli 2011). "Tyneside 7/7 bombings survivor Lisa French has been contacted by detectives investigating News of the World phone hacking scandal". ChronicleLive. Hentet 16 september 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ "London bombing survivor threatens to sue over hacking". Kent News. 8 juli 2011. Hentet 16 september 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ Susan Ryan (7 juli 2011). "Warnings of potential Irish victims of NOTW phone hacking". Thejournal.ie. Hentet 16 september 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ (7 July 2005). "Union Flag to Fly at Half-Mast". UTV. Retrieved 4 September 2007.

- ^ (10 July 2005). "Europe to Mark Tragedy With Two Minutes of Silence". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 September 2007.

- ^ (1 November 2005). "Tributes Paid to Bombing Victims". BBC. Retrieved 4 September 2007.

- ^ (7 July 2006). "Nation Remembers 7 July Victims". BBC News. Retrieved 4 September 2007.

- ^ "Tributes paid at 7 July memorial". BBC News. 7 juli 2009.

{{cite news}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ Tran, Mark (7 juli 2014). "7/7 survivors condemn defacement of memorial on ninth anniversary". The Guardian. Hentet 7 juli 2014.

{{cite news}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ "President Signs Book of Condolence at British Embassy". whitehouse.gov. 8 juli 2005. Hentet 16 april 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ (7 July 2005). "U.S. raises terror alert for transit systems – 7 July 2005". CNN. Retrieved 16 April 2008.

- ^ Dodd, Mike (13 juli 2005). "Rating the game: Clemens, dugout humor spice it up". USA Today. Hentet 15 januar 2010.

{{cite news}}: CS1-vedligeholdelse: Dato automatisk oversat (link) - ^ (8 July 2005). "No Known New Zealand Casualties in London". tvnz.co.nz. Retrieved 4 September 2007.

- ^ (1 September 2005). "Half Masting of the Flag". Canadian Heritage. Retrieved 4 September 2007.

- ^ (3 September 2009). "[1]". Australian National Flag Association. Retrieved 6 February 2011.

- ^ (12 July 2005) "Government Calls for Two Minutes Silence", and in Cyprus. Department of the Taoiseach. Retrieved 4 September 2007.

- ^ (13 July 2005). "Spain Royal Guard Honours London". BBC. Retrieved 4 September 2007.

Further reading

[redigér | rediger kildetekst]- Books

- Official reports

- Greater London Authority report (PDF)

- House of Commons report (PDF)

- Intelligence and Security Committee report – May 2006 (PDF)

- Intelligence and Security Committee report – May 2009 (PDF)

- Medical report

- The account of the doctor leading the team at the scene of the Tavistock Square bus bomb. Retrieved 11 August 2005

- Radio broadcasts;

- The Jon Gaunt show originally broadcast live at 9:00 am on 7 July 2005 on BBC London. First mention of events at approximately 27 minutes into the broadcast.

- Photos

Eksterne henvisninger

[redigér | rediger kildetekst]- Official inquest transcripts

- 2016 BBC News interview with the brother-in-law of Mohammad Sidique Khan

| Wikinews: Coordinated terrorist attack hits London – relateret nyhedssag på engelsk |

|

Wikiquote har citater relateret til:

[[q:{{{1}}}|Kalaha/sandkasse1]].

|

| Denne artikel kan blive bedre, hvis der indsættes geografiske koordinater Denne artikel omhandler et emne, som har en geografisk lokation. Du kan hjælpe ved at indsætte koordinater i wikidata. |